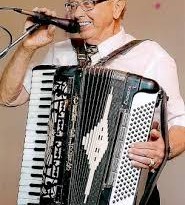

Berlyn Staska: A man and his music

By Jeffrey Jackson

OWATONNA — For nearly as long as he can remember, Berlyn Staska has held a horn in his hand.

And that’s a long time.

Staska first picked up a horn — a silver Sears & Roebuck cornet, he remembers — when he was 6 years old. Now, more than 80 years later, Staska still practices the trumpet 30 to 45 minutes every day, still plays in the Owatonna Community Band that he helped formed, and still plays taps at local military funerals and veterans’ events.

For the record, he doesn’t seem ready to slow down any time soon.

“If you keep active, you live longer,” he said.

It seems to be working. Staska is 87 and will turn 88 come May. And throughout those near 90 years, music has been a part of Staska’s life.

There’s little wonder to that. The encouragement to play music came from his father, a creamery operator in Steele Center who played both trombone and bass in an Army band during World War I. Staska’s father also played with numerous local bands when such bands were popular — the Elks Concert Band, the Elks Kibitzer Band, the Klecker Family Band and a band called the Golden Aces, as well as other local bands.

So there isn’t wonder that about the time Staska was 6, his father put that silver Sears & Roebuck cornet in his hands and a saxophone in the hands of Staska’s younger brother Norman, and they started to play together

“He wanted us to keep up with music,” Staska said.

And in the evenings they would play all kinds of music, from old-time music like marches, polkas and waltzes to what was then “modern” music from the big band era. Sometimes his sisters Janet and Colleen would join in on the accordion or his youngest sister, Sandra, on the piano.

Though he learned a lot, especially learning to love music, during those early formative years, it wasn’t until he got into high school that his music really took off, inspired greatly by the man who Staska calls “the greatest director” that he ever had.{h3}Making music{/h3}In 1936 — a scant two years after a young Berlyn Staska had first taken up the cornet — another cornet player and his wife, who also played the cornet, mov ed to Owatonna and eventually changed not only the face of music in the town, but also business and industry. That man’s name was Harry Wenger.

But before Wenger created the company that bears his name to this day, he was a band teacher and the leader of the music department at Owatonna High School, tinkering in his basement, trying to create a better conducting baton or music stand. It was in this era — the early 1940s, when Wenger was leading the band, the choir and the orchestra to first-place titles in national competitions — that a youthful Staska came under Wenger’s tutelage.

“Harry Wenger was my music teacher — the greatest director I ever had,” Staska said.

And what made Wenger so great in the eyes of this budding musician?

“He was helping, always talking to you if you had problems with the music,” Staska said.

It must have taken because while he was in high school, Staska and his brother Norman, who also played clarinet, got together with four other high school musicians — Phillip Johnson, Don Andersen, Elmer Ackerman and Merle Panzer — to form a clown band under the name “The Hungry Five and One Left Over.”

Staska, of course, played trumpet, his brother on clarinet, as was Johnson, Andersen played the bass, and Ackerman on trombone. As for Panzer, he was the “front man” and didn’t play an instrument. The band, decked out in outrageous costumes and wearing clown makeup, would play for various events, generally marches and so-called “hungry five” music — a sort of German oom-pah music.

“We’d play a few bars with jokes in between,” said Staska.

And the jokes, that’s where front man Panzer came in.

But Staska didn’t limit himself to the high school band or to the Hungry Five. He played in the high school pep band and, in his senior year, with the Owatonna Elks Band.

In 1945, as Staska was nearing the end of his high school days — he graduated from Owatonna High School in 1946, the same year that Harry Wenger officially formed the Wenger Corporation — he and his brother, back on saxophone, started a band playing old-time music, along with Marion Simon on the piano, Marcella Simon on the accordion and Eddie Hrdlichka on the drums.

But the brothers wanted to take a different musical route. So about a year later, that initial band reformed with new personnel — except for the Staska brothers, of course — and a new style of music. Not only did they add more instruments — up to three saxophones, two trumpets, drums, piano and bass — but they also added more modern music from the Big Band Era to their repertoire.

“We played both old-time and modern music,” Staska said, “and played for many high school proms and high school homecoming dances.”

Their gigs were played mostly in the southern part of Minnesota — Faribault, Lonsdale, Waseca, from as far north as New Prague to as far south as Austin and Albert Lea, as far east as Rochester and as far west as Mankato. And, of course, the band — dubbed the Norm Staska Band — played in various venues in Owatonna — the American Legion and the VFW, the Eagles and the Monterey Ballroom, just to mention a few.

“For about five years, we averaged about three nights a week,” Staska said.

But that was by night. By day and by then out of high school, Staska had to find another job.

Life without the horn

The first job that Staska took out of high school was a stock boy for the F.W. Woolworth store in downtown Owatonna — a job which he kept for just a short time, but which would foreshadow several of the jobs that he would have throughout the rest of his working life.

But he didn’t keep that Woolworth’s job for long, choosing instead to take a different job with a company that dealt with a product closer to his real love — music. The Stephenson Music Company, based in Austin, opened a store on North Cedar in Owatonna.

“They sold music and hired a guy to repair radios,” Staska said.

So for about 11⁄2 to 2 years, Staska was a clerk in the store and helped to repair radios.

He left the music company when he had the opportunity to go to work for the Minnesota Highway Department in various roles, finally ending up in the stock room as a stock clerk. The job may have lasted longer except for the distant rumblings of war.

The ongoing tensions between North and South Korea finally exploded in the summer of 1950 when North Korea invaded South Korea. And with the outbreak of the Korean War, Staska knew it was only a matter of time before he was drafted.

Staving off that eventuality, Staska, his brother Norman and a friend spoke to the draft board and were released from the draft so that they could enlist. And enlist they did. On Oct. 7, 1950, Berlyn and the friend were accepted by the United States Air Force. Norman did not meet the requirements of the Air Force and walked across the hall where he was accepted by the Navy. Norman played in a Navy band.

Still, music was not far from his mind.

Even as he went into the Air Force, Staska had hoped that he would be selected to play in the elite Air Force. And he had a shot at it. He auditioned and passed the tests for getting into the band. But he was told that getting into the band was difficult, especially since they had “plenty of trumpet players.”

Case in point: While he was in basic training, Staska met two other trumpet players whose names he still remembers — Bill Hodges and Larry Taine. Taine had played with the Stan Kenton band before the war. And Hodges? Hodges had played in the big bands of the Dorseys, both of them, Tommy and Jimmy. They were in basic training, Staska said, only to get it on their records. Both men auditioned for and were selected to play with the Air Force’s dance band, the same band that Glenn Miller had while he was in the service in World War II.

Instead, the Air Force took advantage of Staska’s other experience, first stationing him as a stock clerk at Westover Air Force Base in Holyoke, Massachusetts, then in procurement and supplies — and teaching the job to other airmen — at F.E. Warren Air Force Base in Cheyenne, Wyoming.

Between those two assignments, Staska took leave in March 1951 to marry Kathleen Evans that he met — where else? — at a dance at which he was playing just south of Owatonna at the Monterey Ballroom.

“There were eight dance bands in town,” Staska said, “and we were playing at a battle of the bands at the Monterey.”

Staska’s tour of duty with the Air Force officially ended on Oct. 7, 1954, four years to the day that he had enlisted. By the armistice had been signed, bringing the Korean War officially to an end.

But the end of the war also meant that “jobs were awfully hard to find,” Staska said. He went to Denver seeking employment, but there were no jobs to be had.

“I thought of re-enlisting,” he said.

But then can a phone call from Owatonna with a job offer with Owatonna Tool Company, or OTC, as everybody called it. It was a working relationship that would last for 36 years, first in the forge shop, then into chrome plating, then to shipping, then inventory control, and finally to purchasing, where he worked as a buyer for 33 years until his retirement in 1990.{h3}Picking up where he left off{/h3}If his four years away from bands during his military service impinged on Staska’s musical ability, you couldn’t tell it. No sooner had he returned to Owatonna than he picked up his trumpet and started to play with local bands — a lot of local band, almost too many to count. And it’s something he hasn’t given up to this day, even though that style of music may not be as popular as it was back then.

He once again started playing with the Elks Concert Band, a band with which he had first started playing back in the mid-1940s, when he was still in high school and a band that used to play at Owatonna’s Central Park on Saturday nights.

In addition to the concert band, the Elks also mounted a clown band — similar to, but larger than The Hungry Five and One Left Over of his youth — known as the Elks Kibitzer Band. Staska played with that band until it disbanded.

Shortly after he returned from the service, he played old-time music with Luverne’s Concertina Band, also doing the arrangements for the band — a relationship he maintained for 18 years. He also played music, mostly marches, with a brass group started by Ladd Rypka known as the Brass Renegades. He played with the Klecker Family Band, the Golden Aces and with the concert band of the American Federation of Musicians Local 490.

In the mid-1980s, when Staska was nearing 60 years old, he and a group of local musicians got together and formed a big band, playing the music of the 1940s and ‘50s.

“The band was called the River City Big Band, and we played for local dances and concerts in the parks,” he said.

Then there was — or rather “is” — what may be perhaps his crowning achievement, the Owatonna Community Band. In 1977, Staska, along with Rufus Sanders, Dave Leach and John Holland, formed the band, which, over the years, has played concerts around the surrounding area. The band also started concerts downtown in Central Park, concerts that have grown into the 11@7 concert series. The band, nearly 40 years old now, still boasts Staska as one of his members.

Along with the Owatonna Community Band and about the same time, the Owatonna Community Orchestra, directed by Arnold Kruger, was formed. Staska also played with the orchestra.

And there also is his solo work of a much more somber note.

For the past 35 years, Staska has been a bugler for the Steele County Military Honor Guard playing Taps. He estimates that he has played Taps for about 2,500 military funerals.

He has been honored for his musical contributions, once in 2008 when he and Armond Rezak were honorable chairpersons for the Music in Owatonna concert series, which that year featured a performance of big band music by the Glenn Miller Orchestra at the Owatonna Degner Regional Airport. Then in 2015, he was the grand marshal for the Harry Wenger Marching Band Festival in Owatonna — named for his former teacher.

More than just music

But that is not all that Berlyn Staska has done for his community, especially since his retirement in 1990. And sometimes he volunteer reaches far beyond the boundaries of Steele County.

Beginning in 1992, Staska, through his church, Associated Church in Owatonna, started working with Habitat for Humanity — an association that has taken him as far as Paducah, Kentucky to help build houses and an association that has led him to be a building supervisor on homes here in Steele County.

Also through the church, he has gone on mission trips to help with flooded areas in Gulf Port, Mississippi, Cedar Rapids, Iowa, Minot, South Dakota and Minneapolis.

Closer to home, he’s been an active member in the Kiwanis Golden K Club here in Steele County, serving as its president in 1994-95, his work for which earned him the Distinguished President’s Award from the national office.

He also served on the City of Owatonna’s Building Code Board of Appeals.

And he attributes it all to his wife, Kathleen, who helped set up the local Meals on Wheels program, now in its 44th year, organized the Crisis Resource Center and served for 11 years on the Steele County Planning Commission — all of which earned her the Book of Golden Deeds recognition from the Owatonna Exchange Club in 1991.

“She got me started volunteering,” he said.

As for himself, Staska’s efforts have been recognized as well. In 1998, he was named Senior Citizen of the Year by the Steele County Free Fair, going on to place second at the Minnesota State Fair. Then in 2005, he was recognized by the SCFF with the same award again.

On Aug. 25, 2010, Staska was awarded the prestigious Virginia McKnight Binger Award from the McKnight Foundation along with five others — an award that with a $10,000 prize for the recipient to use as he or she wished.

“I donated to my church, the Steele County-Waseca County Habitat for Humanity and other local organizations,” he said. “The two out-state winners were a woman from Duluth and myself.”

As he said, “If you keep active, you live longer.”

Berlyn Staska has certainly proven that to be true.